If the pick-up in capital spending among businesses continues, higher prices are much more likely to be here to stay, says Pendal’s head of global equities Ashley Pittard

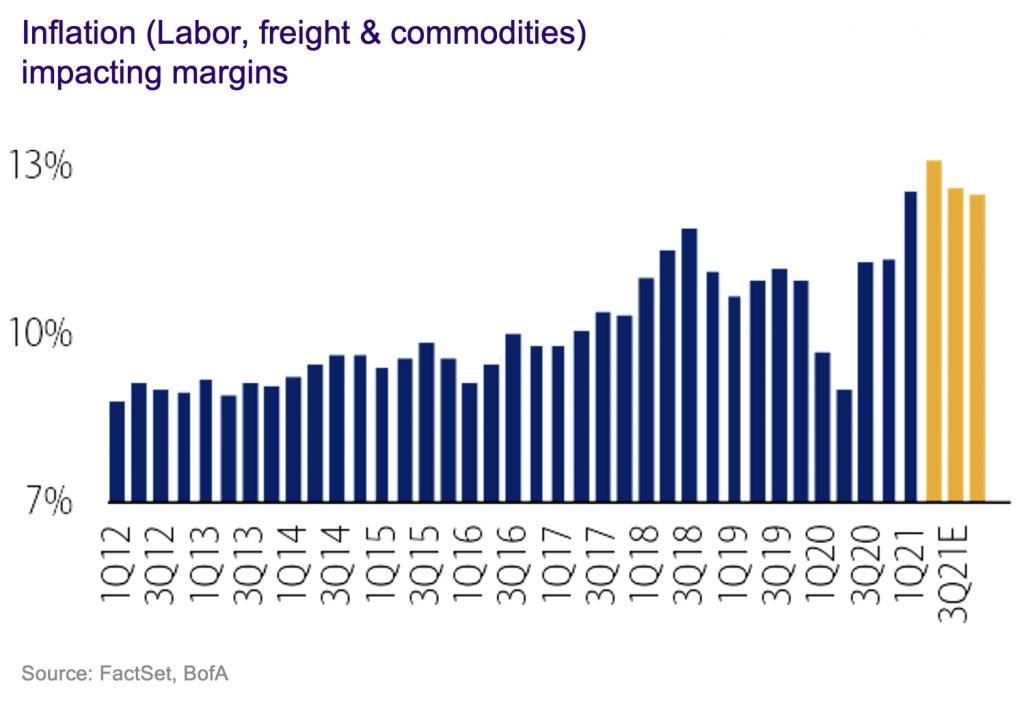

- Capital spending can trigger longer term, sustainable inflation

- Big rises in profit margins spur businesses to invest

- Evidence points to inflation shifting from transitory to structural

CAPITAL spending is the dark horse in the debate on inflation, says Pendal’s head of equities Ashley Pittard.

Wage and transport costs and consumer spending tend to grab the headlines. But capital investment by business, with long lead times, can provide a significant, sustainable fillip to prices.

“If we start seeing capital expenditure re-rating year on year, that will solidify inflation coming through,” says Ashley Pittard, head of Pendal’s Global Equities boutique.

“In the first quarter of this year capex was mixed in the United States. But in the second quarter it was the strongest capex since 2004.”

The prospect of inflation remains the big question in financial markets: is it transitory or structural?

Central banks around the world have mostly argued it is transitory. But in recent weeks the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Reserve Bank of Australia, among others, have spoken of winding back bond purchase programs.

If the pick-up in capital spending continues, higher prices are much more likely to be here to stay.

Businesses, particularly in Europe and North America, are willing to invest because of the earnings boosts they’ve experienced in the first half of this year — and based on improved profit margins.

“Earnings growth is up almost 100 per cent across the S&P500 for the June quarter, but sales growth was up only 27 per cent,” Pittard says.

“In Europe, the sales growth was 28 per cent, which is very similar, but the earnings growth was 243 per cent.”

Europe’s outperformance partly reflects the mix of sectors with energies and financials higher contributors to European bourses. Those sectors have done very well with commodity prices rising, and relatively few bad debts to deal with for the banks.

Also, Europe started from a lower base and had more scope to climb, Pittard says.

“Earnings have been strong year-on-year and against 2019. But companies are also getting massive margin expansion and in some cases the highest margins ever,” he says. “This is encouraging capital spending which is adding to inflation.”

Find out about

Pendal Concentrated Global Share Fund

Price rises are already coming through with US inflation up 7.8 per cent in July, German inflation at 3.4 per cent (the highest rate since 2008) and Spain at 3.3 per cent.

“You are seeing Europe getting inflation in the mid threes. You have the US with inflation well above 5 per cent,” Pittard says.

For businesses, when borrowing is so cheap, and earnings are rising, they pay down their debt quicker and can invest more, he says.

If the investment is productive it can eventually reduce inflation. But in the short-to-medium term it will put pressure on prices.

Capital spending adds another piece of the argument that inflation is more than transitory.

“There is no doubt it is a timing issue before transitory inflation becomes structural inflation,” Pittard says.

About Ashley Pittard and Pendal Concentrated Global Share Fund

Ashley Pittard leads Pendal’s Global Equities investment boutique. He is responsible for setting the strategy, processes and risk management for the boutique and its funds including Pendal Concentrated Global Share (COGS) Fund.

Ashley has more than 24 years of finance experience, including roles in petroleum economics, global energy investment analysis and 20 years as a global equities fund manager.

Pendal COGS Fund is an actively managed, concentrated portfolio of global shares diversified across a broad range of global sharemarkets.

Find out more about Pendal Concentrated Global Share Fund

Pendal is an independent, global investment management business focused on delivering superior investment returns for our clients through active management.

Much of the confusion about ESG stems from three questions. Here Regnan senior ESG and impact analyst MURRAY ACKMAN explains the answers

- Diversity targets are often flawed

- But DEI is a good indicator of how well a company is managing risk

- Find out about Regnan Credit Impact Trust

- Find out about Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest fund

ESG can be pretty confusing for investors.

The acronym (which stands for Environmental, Social and Governance issues) refers to a jargon-filled investment space which requires an understanding of regulations, methodologies and taxonomies.

And the more ESG evolves, the more complicated it becomes for investors trying to judge the effect of these criteria on their investments.

Why is ESG so confusing? How can you see through the noise?

Much of the confusion about ESG stems from three questions facing investors.

Here we’ll try to explain them.

1. Are we looking at the same thing?

Third-party ESG data providers often have different views and methodologies for rating different companies.

That means ESG data requires more interpretation than, for example, balance sheets or credit ratings.

Credit rating agencies may offer different ratings — but they largely analyse the same numbers from financial statements.

An ESG report can include absolutely everything that has an impact on the macro, meso and micro environmental, social and governance risks a company may face.

There is also the overwhelming challenge of conflation.

A fossil fuel extraction company may be managing its risks reasonably well — but if investors don’t want to invest in fossil fuels then it seems rather irrelevant.

2. Are you saying what I think you’re saying?

Everywhere we see advertisements aimed at convincing people that if they invest with a particular manager they’ll be able to save the world.

To combat this kind of hyperbole, regulators and gatekeepers have stepped in to reduce potentially misleading and deceptive conduct.

Find out about

Regnan Credit Impact Trust

This includes education for clients, longer caveats and attempts at standardising terms such as “sustainable investing”.

For investors, this means more surveys, greater reporting, a focus on data and ensuring proper systems are in place.

Regulators are pushing for standard language and consistent data to help people understand what’s being said.

That’s a positive step — but more education, more disclosure and more reporting are not enough. People don’t read every food label before eating.

Now ESG is starting to be viewed less as a marketing problem and more as a compliance challenge.

At Regnan, we continue to strongly believe that including ESG criteria in the investing process provides more information to make better investment decisions.

3. Does ESG actually affect investment decisions?

Are ESG consideration linked to reality? Does it do what clients actually want? Do ESG funds outperform?

You should be able to find ESG integration statements on most big asset manager websites which outline how they include ESG considerations in their decision making.

Realistically, sometimes ESG considerations might have only a limited influence on an investment decision. But this differs across asset classes.

For example, omitting energy stocks that gained significantly would’ve made outperformance difficult for some equity strategies over the past two years. But it would have had little impact on fixed income.

How much ESG is included in investment decision-making is ultimately up to clients.

Do you want to invest to make a more sustainable economy and potentially avoid some risks? Or is performance the only thing that matters?

At the end of the day, fund managers, super funds and financial planners are all trying to serve the needs of their clients.

What approach is best? It’s about working out what ESG does for different clients.

Some might hate anything that suggests companies need to consider the environment. Some might not want to make the world worse. Others may want to make the world a better place.

These are values judgements.

Here’s a very simply way I explain ESG investing:

- If you only care about performance, that doesn’t necessarily mean you should ignore ESG funds. Some ESG funds are top performers across the board. ESG approaches may also highlight non-financial risks that can become financial risks.

- If you want to avoid investing in bad stuff, focus on a fund that has negative screens (eg no tobacco producers or controversial weapon makers). What is considered bad may differ between clients, but these type of screens are becoming more uniform.

- If you prefer to invest in good stuff, look for funds that have some kind of process for selection of investments, and some kind of measurement on what those investments are doing.

- If you want really good stuff, look for something that explicitly addresses “impact”. There may be more novel strategies available, but there will likely be trade-offs such as having funds locked-up or high volatility in performance.

It’s natural for clients to be apprehensive about ESG because it’s a new topic full of technical words. But while there are definitely some parts that need more work, there are quite a few of us working on improvements.

About Murray Ackman and Regnan

Murray is a Senior ESG and Impact Analyst with sustainable investing leader Regnan.

He also provides fundamental credit analysis on Environmental, Social and Governance factors for Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

Murray has worked as a consultant measuring ESG for family offices and private equity firms and was a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace where he led research on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Find out more about Regnan here

Regnan Credit Impact Trust is an investment strategy that puts capital to work for positive change.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund is an Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

Some billionaires argue diversity, equity and inclusion policies are a bad thing – and could even cause plane crashes. Pendal’s MURRAY ACKMAN explains why they’re wrong

- Diversity targets are often flawed

- But DEI is a good indicator of how well a company is managing risk

- Find out about Regnan Credit Impact Trust

- Find out about Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest fund

AMERICAN billionaires seem to be picking fights with big brands and civil rights groups over whether corporate diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) policies are discriminatory.

Or even whether they cause aircraft malfunctions.

If you’ve been following the “woke backlash”, you’d be familiar with recent flash points such as the campaign against Harvard’s first Black female president Claudine Gay.

Tesla’s Elon Musk, hedge fund manager Bill Ackman and Lululemon founder Chip Wilson have all been engaging in civil discourse on social media recently, expressing anti-DEI views.

Musk went as far as suggesting that Boeing, fresh from having a fuselage panel fall off mid-flight last month, was prioritising diversity over safety. That drew a swift rebuke from civil rights groups.

“DEI must DIE,” Musk said recently on his X social network. “The point was to end discrimination, not replace it with different discrimination.”

This week the Tesla CEO erased mention of DEI in the electric vehicle maker’s corporate filings.

Find out about

Regnan Credit Impact Trust

Do DEI critics have a point? And what does that mean for investors and companies?

What are the concerns about DEI?

Musk’s criticism of Boeing centred around the impact and unintended consequences of connecting executive pay to diversity targets and ESG metrics.

At the start of 2022 Boeing altered its bonus scheme, rewarding executives who hit certain climate and DEI targets.

Boeing is certainly not alone here.

In 2011, just 1 per cent of listed companies had such a policy. By 2021 it was 38 per cent, and the trend continues.

Supporters argue this is positive for companies and shareholders.

The idea is that such policies safeguard future economic results from risks while aligning the managerial objectives with shareholder interests.

Sharemarket analysts look for such policies as a sign that a business cares about a particular issue.

Who’s right?

Does linking executive pay to diversity improve a business? Or are such corporate DEI policies a sign of excess?

There are plenty of studies – including from Pereptual’s Regnan sustainable investing business – suggesting DEI can drive business outperformance.

A 2021 study from sustainable investing leader Regnan found that DEI – and especially equity and inclusion – can drive business outperformance.

A series of McKinsey & Company reports found “not only that the [DEI] business case remains robust but also that the relationship between diversity on executive teams and the likelihood of financial outperformance has strengthened over time”.

Yet Regnan also found many businesses think about diversity and inclusion in a flawed way. For example, DEI policies often focus on the needs of minority groups, while majorities are not always adequately considered.

For investors and companies alike, we believe organisational settings should allow all talent to flourish – including ‘majority talent’ as well as talent that is traditionally under-represented.

These are essential pre-requisites for an equitable and inclusive workplace. Businesses benefit from fair employment practices, supportive cultures and open decision-making.

What it means for investors

While there is now a lot of ESG measurement going on inside companies, it’s fair to say there could be a deeper discussion about how inclusive culture can be good for a business.

But is Elon Musk right to say there is undue focus placed on DEI?

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund

An Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

The billionaire’s complaints could make sense in the context of a boot-strapped start-up operating from the proverbial garage.

But it feels provocative coming from the CEO of a business with one of the highest market caps in history.

Based on our experience at Pendal, businesses clearly demonstrate what they care about by what they report.

And that is useful for investors.

Investors should expect to see comprehensive DE&I plans from companies. And take caution with companies that ignore these responsibilities.

And they should look beyond the reported diversity numbers to understand if a business has the right structure to allow for diversity and growth.

While it’s entertaining to see billionaires argue among themselves, investors must understand how a company thinks about diversity and inclusion if they want to understand whether it is managing risks.

About Murray Ackman and Regnan

Murray is a Senior ESG and Impact Analyst with sustainable investing leader Regnan.

He also provides fundamental credit analysis on Environmental, Social and Governance factors for Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

Murray has worked as a consultant measuring ESG for family offices and private equity firms and was a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace where he led research on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Find out more about Regnan here

Regnan Credit Impact Trust is an investment strategy that puts capital to work for positive change.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund is an Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

A global taskforce backed by Australia aims to shift global financial flows away from ‘nature-negative outcomes’. Pendal’s MURRAY ACKMAN explains

- Investors need to consider biodiversity

- Agriculture, food sectors impacted most

- Find out about Regnan Credit Impact Trust

- Find out about Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest fund

MORE than half of global GDP depends on natural resources — and these days investors are well aware of biodiversity risk when making portfolio decisions.

Now a group of companies representing the sectors most exposed to the impact of nature loss has come together to guide investors away from what they call “nature-negative outcomes” towards “nature-positive outcomes”.

The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) is made up of representatives from 40 organisations in sectors such as agribusiness, the blue economy (ocean resources), food and beverage, mining, construction and infrastructure.

It’s also backed by the Australian federal government — which has provided funding and participated in pilot programs.

New guidelines

In September, the taskforce issued a set of guidelines which aims to integrate nature into decision-making and give organisations a complete picture of their environmental risks,” says Pendal ESG credit analyst Murray Ackman.

It is, in part, a consequence of greater disclosure requirements around environmental risks, Ackman says.

“More than half the world’s GDP is estimated to depend on biodiversity and ecosystem services.

“Fresh water, fertile soils, clean air and even insects pollinating plants — the flow-on effects of the degradation of biodiversity are immense.

“As we become more aware of threats such as climate change, we’re beginning to understand how interrelated everything is.

“The framework is still emerging, but people are hoping biodiversity risk will become tied into a company’s social licence.

A global initiative

Investor focus on biodiversity has intensified in the past couple of years as regulation evolves to combat prevent “greenwashing”.

“The TNFD is a new global initiative which aims to give financial institutions and companies a complete picture of their environmental risks,” Ackman says.

“Biodiversity should be considered in managing business risks, and also in terms of system wide risks. It can can be seen as a proxy for resilience.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund

An Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

“Companies that have an understanding of their biodiversity risk are more likely to have a multifaceted understanding of all their risks.

“Some sectors are more impacted than others. There is a more immediate effect on agriculture than on business software providers, for example.”

Investor influence

Already some big investors are using their influence to push companies to understand their biodiversity risk.

Though insisting that all companies spend time and resources deep-diving into biodiversity risk might not be an optimal outcome, says Ackman.

“At Pendal, our focus is on direct risks in certain sectors like agriculture or sectors involved in selling food.

“We focus on the angels and demons — the extremes. We look at the sectors with a huge risks.

“On the angel side, we’re looking for solutions to some of the biodiversity challenges. That includes investing in World Bank bonds.

“In other sectors, biodiversity risk falls under the broad umbrella of whether a company is managing credit risk in general. Are they managing all their potential risks?” Ackman says.

Find out about

Regnan Credit Impact Trust

Pendal has invested in a Biodiversity and Sustainable Development bond from the World Bank, which has an explicit focus on biodiversity.

“This bond is helping to put nature as central to development through promoting conservation, training, and policy to seek nature-based solutions in agriculture, forestry and fisheries.

“We view biodiversity as more than just another risk reporting framework.

“We see it as an opportunity to invest in solutions, and we’re optimistic that we will see more ways to bring about development and environmental outcomes through these types of investments.”

About Murray Ackman and Regnan

Murray is a Senior ESG and Impact Analyst with sustainable investing leader Regnan.

He also provides fundamental credit analysis on Environmental, Social and Governance factors for Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

Murray has worked as a consultant measuring ESG for family offices and private equity firms and was a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace where he led research on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Find out more about Regnan here

Regnan Credit Impact Trust is an investment strategy that puts capital to work for positive change.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund is an Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

There’s a dearth of true ‘social bonds’ in the market, but the reward for issuers can be great, explains Pendal ESG credit analyst MURRAY ACKMAN

- Pendal believes social bonds should serve the underprivileged

- Find out about Regnan Credit Impact Trust

- Find out about Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest fund

MOST social bond investors have the same aim: to make money while making a positive difference in society.

An example is the federal government’s National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation, which last year issued almost $200 million in social bonds, making returns for investors while providing cheap funding for social and affordable homes.

But not all social bonds are equal when it comes to use of proceeds, cautions Murray Ackman, a credit ESG analyst with Pendal’s income and fixed interest team.

“At the heart of social bond issuance is what the proceeds are is used for,” says Ackman.

“At Pendal, we want the proceeds to benefit the under-served. In the social bond market, that isn’t always the case.”

Not all social bonds are equal

The term ‘social bond’ has different meanings to different investors.

Social bonds are defined by The International Capital Market Association as use of proceeds bonds that raise funds for new and existing projects that address or mitigate a specific social issue or seek to achieve positive social outcomes.

But Pendal takes a more refined view, focusing on bonds that benefit the underprivileged.

“It means that we run into the risk of the proceeds of social bonds not being allocated as we’d want,” says Ackman.

“An issuer might promoted a ‘social bond’ — but it may not meet our criteria of helping the underserved in society.”

“For example, we’ve seen so-called ‘social bonds’ where proceeds have gone towards anyone impacted by Covid. That’s everyone.”

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund

An Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

“In the Netherlands, around 70 per cent of the population is eligible for some kind of social housing.

“So, the Dutch Housing Authority can do a ‘social bond’ — but that’s not going to fit our criteria.

“Our view is clear. A social bond should be an instrument to serve the underprivileged in society.”

‘True’ social bonds in demand

Availability of ‘true’ social bonds is contricted in a market where demand already outstrips supply.

Ackman believes issuers could do more to expand the market.

“Managers are looking for social bonds, not just because they want to bring social change, but also because there is so much demand for them, they will perform well in the secondary market,” Ackman says.

Social bond issuance is an area where supra nationals, such as the World Bank, play a large role, and semi-governments (typically state governments) can play a bigger role.

“If state governments are issuing social bonds, they need to target the underserved. Proceeds used to upgrade schools might not fit the definition, because that is just what state government do.

Find out about

Regnan Credit Impact Trust

“What’s more interesting is if the proceeds are used to provide more accessible schooling for the disabled, or new schools are built in regional and remote communities,” Ackman says.

Imapact of social bonds can be hard to track

There is also a challenge in reporting because established benchmarks might not be available.

“With green bonds you can report emissions avoided, or renewables generated, but in social bonds it can be much more bespoke. That’s fine for our purposes, though. We want to invest in projects that make meaningful change and a positive social contribution to society.”

Given the challenges in the market, and high demand, Ackman says issuers need to become more creative in how they bundle together bonds.

“We’d love to see a big bank that lends to ‘for-purpose’ organisations — those driven by a social mission, rather than profit — to pull a whole bunch of loans together and issue a social bond.

“That would benefit from a big bank credit rating, make it safer to invest in, and have a great social purpose attached. It’s happening in green bonds, and it would be good to see it in social bonds.”

“There are a lot of challenges that come with social bonds, but the demand is there.

“It is up to the issuers to meet that demand.”

About Murray Ackman and Regnan

Murray is a Senior ESG and Impact Analyst with sustainable investing leader Regnan.

He also provides fundamental credit analysis on Environmental, Social and Governance factors for Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

Murray has worked as a consultant measuring ESG for family offices and private equity firms and was a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace where he led research on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Find out more about Regnan here

Regnan Credit Impact Trust is an investment strategy that puts capital to work for positive change.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund is an Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

The WA government – a mining superpower – just announced a green bond. Here Pendal’s MURRAY ACKMAN explains how to size up obvious, and not-so-obvious, sustainable fixed interest opportunities

- Not all green bonds are equal

- Find out about Regnan Credit Impact Trust

- Find out about Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest fund

AUSTRALIANS invest some $25 billion a year in local green, climate and social impact bonds, according to the Responsible Investment Association’s latest benchmark report.

But only some of these bonds meet the highest standards of sustainable investors. And it’s not always obvious which ones.

Consider these three examples of recent sustainable bond issuers:

- A national electricity network connecting renewables to the grid

- A telco giant reducing power consumption on its network

- Mining super-power Western Australia — the only Australian state that emits more carbon now than it did in 2005

You may be surprised to learn that only the WA bond – announced last week – met with the approval of Pendal’s income and fixed interest team.

“The key to investments like this is understanding the ‘but for’ test,” says Murray Ackman, a credit ESG analyst in Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

When assessing a new sustainable bond, Murray likes to ask “but for my investment, would this project exist?”

In other words, is the bond simply funding “business-as-usual” activity? Or is it truly making an impact?

“We target green bonds with greater impact,” Ackman says.

Example: electricity distribution network

Ackman uses the example of an electric power distributor where the answer to the “but for” test was “no”.

In this case, the raised funds were earmarked for the replacement of decades-old copper wire, and installation of new high-voltage lines and substations.

That activity supports the transition away from fossil fuels to renewables and reducing carbon emissions.

“But the problem for us is this: connecting generation to the grid, while very important, is very much business-as-usual for a grid owner,” says Ackman.

“Their job is to connect things to the grid.

“Claiming it’s green is kind of like a highway boasting about higher EV usage.”

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund

An Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

Example: NBN’s green bond

At the National Broadband Network, a $2 billion-plus green bond has been issued to fund a reduction in the emissions generated by Australia’s broadband internet infrastructure.

“Their argument is that fibre optics are more efficient than copper, and so replacing copper with fibre reduces emissions,” says Ackman.

“That may well be true, but it just so happens that their business model also relies on fibre optics, because that means higher internet speeds that they can charge more for.

“There is also the Jevons Paradox to consider — the more efficient something is, the more usage it generates, paradoxically leading to an increase in consumption.

“The NBN’s assumption is electricity usage will go down because the network is more efficient. But if we all watch more Netflix with our higher speed internet, than usage will go up.”

WA’s green bond

So where does that leave WA?

Find out about

Regnan Credit Impact Trust

WA’s green bond is raising $1.9 billion to decarbonise the state’s electricity grid by investing in battery storage and wind farms alongside charging infrastructure and rebates for electric vehicles.

“For WA, the complaint we get is ‘how can you invest when they dig up so much stuff?” says Ackman.

“The first thing we say is that the stuff that they are digging up is very different to the coal mining that happens in the east coast states. WA’s miners are producing metals like iron ore and lithium spodumene that are essential resources for the transition.

“And the projects funded by the green bond are going to move the dial on the energy transition.

“WA’s policies have progressed significantly, and this green bond is a reflection of that.”

Ackman says the WA projects pass the ‘but for’ test.

“The newness is a huge component of it,” he says.

“A green bond needs to be evidence of your policies — not an apology for them.

“WA’s green bond follows a year after the government’s new sustainability plan and is reflective of the focus of the government to green up their economy and green up their energy usage.

“That’s something that we want to support.”

About Murray Ackman and Regnan

Murray is a Senior ESG and Impact Analyst with sustainable investing leader Regnan.

He also provides fundamental credit analysis on Environmental, Social and Governance factors for Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

Murray has worked as a consultant measuring ESG for family offices and private equity firms and was a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace where he led research on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Find out more about Regnan here

Regnan Credit Impact Trust is an investment strategy that puts capital to work for positive change.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund is an Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

Would you buy a green bond from Albo? Pendal’s MURRAY ACKMAN has a few questions investors should ask before investing in the federal government’s first green bond

- First ever sovereign green bond planned for 2024

- Opportunity to fund catalytic change

- Find out about Regnan Credit Impact Trust

- Find out about Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest fund

THE Albanese government’s plans for a sovereign green bond program will provide an opportunity to spark transformational projects in hydrogen, batteries and biodiversity, says Pendal’s Murray Ackman.

But investors should carefully scrutinise the plan before investing, says Ackman, a credit ESG expert in Pendal’s income and fixed interest team.

Investors will want to reassure themselves that the government is truly responding to Australia’s needs, and not greenwashing poor climate policies or funding projects that would have been financed regardless, he says.

Sovereign green bonds are issued by governments to fund projects that have a positive impact on the environment.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers outlined the plan to introduce a green bond program at last month’s Investor Roundtable, a government forum designed to engage super funds, banks and asset managers.

“The government is planning to issue its first green bond in 2024 and is using it to frame the whole green and sustainability market,” says Ackman.

“They want to show what ‘good’ looks like and to set expectations about these types of issuances, including potentially aligning with other kinds of regulation including climate reporting.

“We are excited to see the government show interest in green bonds. However, not all green bonds are equal.”

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund

An Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

Ackman has developed four key questions for investors to ask as they judge the government’s plans:

1. Is the bond supporting genuinely new projects?

Green bonds must support new projects that encourage further investment in that area, he says.

This could include hydrogen, large-scale batteries, maintaining biodiversity and climate-change adaptation.

Capital recycling, funding projects that already exist and projects that would likely have happened anyway fall short of this test, he says.

“Additionality is the key term — funding something that would not have been funded but for this green bond.”

2. Are the projects truly revolutionary?

Green bonds should fund risky projects with the potential for big impact, Ackman says.

Funding social housing that provides underserved people with housing in energy efficient homes with solar panels that reduce ongoing living expenses would fit the bill, he says.

“Government has a different risk profile to the private sector and that gives it an opportunity to fund catalytic change — things that cause a step change.

“This is what the US has done with the Inflation Reduction Act, creating a market for hydrogen by subsidising it significantly.

“Government has always had a role historically in bringing about significant change — the internet, space travel — there’s always been government money put up to change how things work.

“This is what we want to see from this green bond.”

Find out about

Regnan Credit Impact Trust

3. Is reporting clear and transparent?

The bond issuance should provide an opportunity for the government to set expectations for what meaningful and measurable impact reporting looks like.

“This green bond is an opportunity to put a stake in the ground as to the minimum expectations for reporting and for transparency. This is an evolving space. What was good enough three years ago is not good enough now.

“For the government to say ‘this is this is what good looks like now’ is a powerful thing.”

4. Is the green bond connected to a genuine policy commitment to address climate change?

Finally, Ackman sounds a warning.

Issuing a green bond signals a commitment towards environmental concerns and a promise to continue to support these types of projects.

“Green bonds have a halo effect on the issuer. We will not invest in green bonds from issuers that we do not believe are committed to environmental change and focused on climate stability.

“By issuing a green bond, the Australian Government will be saying that they have a strong commitment.”

Ackman points to Pendal’s exit from a Queensland government green bond after the state’s approval of Indian conglomerate Adani’s new coal mine a few years ago.

“When they approved Adani, we exited the green bond because there was a disconnect between what the green bond was attempting to do and what government policy was attempting to do.

“A green bond should be a reflection of an issuer’s philosophy — not an apology for their actions.”

About Murray Ackman and Regnan

Murray is a Senior ESG and Impact Analyst with sustainable investing leader Regnan.

He also provides fundamental credit analysis on Environmental, Social and Governance factors for Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

Murray has worked as a consultant measuring ESG for family offices and private equity firms and was a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace where he led research on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Find out more about Regnan here

Regnan Credit Impact Trust is an investment strategy that puts capital to work for positive change.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund is an Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

The Albanese government’s revamp of a Coalition-era emissions reduction mechanism raises a number of issues for investors. Pendal’s MURRAY ACKMAN explains

- Winners and lowers from safeguard mechanism

- Find out about Regnan Credit Impact Trust

- Find out about Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest fund

INVESTORS should keep a close watch on changes to a major Australian carbon emissions policy, which could have wide ramifications for the economy and markets, says Pendal’s Murray Ackman.

The Albanese government is aiming for a 43 per cent cut in emissions by 2030 (compared to 2005) and net zero emissions by 2050 — in line with its new climate change law.

To help achieve this, the government is revamping an old Coalition policy known as the “Safeguard Mechanism“, which was designed to reduce carbon emissions by regulating the amount of greenhouse gases that big industrial facilities could emit.

Originally introduced by Tony Abbott’s Coalition government, the mechanism set emissions “baselines” for 215 of our biggest polluters.

Those that exceeded their baseline were required to offset the excess pollution with carbon credits bought from sources that had reduced their emissions.

But critics say the mechanism hasn’t worked. Baselines were too high, the policy was generally not enforced and since then new polluters have started operating.

From July, the Albanese government will strengthen the mechanism in a number of ways, including a 4.9 per cent annual cut on allowable emissions for the biggest emitters.

You can read more about the safeguard mechanism here.

What it means for investors

Investors and companies could be impacted in a number of ways, says Ackman, a credit ESG analyst in Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

Find out about

Regnan Credit Impact Trust

Here are some issues:

1. Policy certainty

“The first thing we’re looking for as investors is policy certainty,” he says.

“One of the challenges for investors is always that policy is proposed and then negotiated with the Greens and cross bench. That uncertainty can spook investors.”

In March, the Albanese government struck a deal with the Greens to implement the safeguard mechanism.

2. The problem with offsets

Under the Safeguard Mechanism, businesses that exceed their baselines can meet their obligations by buying offsets from approved emissions reduction projects.

But sustainable investors will want to take a close look at these offsets, says Ackman.

“There are certain classes of offsets that are pretty dodgy,” he says.

“If you ask a farmer not to clear certain land and get offsets for that, what if they had no intention to clear the land anyway? How do you know it’s not going to be cleared anyway in 10 years?

“Planting trees is also fraught with challenges in Australia — floods, droughts, fires. Just because you plant them doesn’t mean they are going to last to maturity.”

The key for investors seeking to understand the difference between effective and ineffective offsets lies in whether the carbon emission reduction is guaranteed or not, Ackman says.

“One of the offsets allowed in the safeguard mechanism is if you reduce emissions more than target you can sell the excess.

“That seems reasonable because you are measuring something that has actually happened.”

3. New fossil fuel projects can still go ahead

Despite an agreement with the Greens on a hard cap for emissions, the mechanism won’t stop all future fossil fuel projects.

“That’s robbing Peter to pay Paul,” says Ackman.

Modelling suggests emissions from “financially committed new projects” for coal and LNG alone will generate 56 million tonnes of carbon equivalent emissions between 2024 and 2030.

That’s nearly 5 per cent of the mechanism’s entire emissions budget.

That means higher reduction rates could be required from the companies with existing facilities covered by the mechanism.

“This is the complaint of the Greens and the cross bench.

“You need to rule out new fossil fuel production because otherwise the safeguard mechanism is incomplete.”

4. Cost of living pressure

The mechanism is susceptible to cost-of-living pressures.

“Where the rubber hits the road is when these bigger emitters start having an impact on the cost of living,” says Ackman.

He points to two challenges.

“The first is basic supply and demand — if everyone’s doing this at the same time, the costs associated with reducing emissions could be more than we’re expecting.

“The second challenge is that complaints about higher costs in the community could weaken the government’s resolve.

“Every government has strong ideology until its starts to hurt the hip pocket.”

Winners and losers

The safeguard mechanism has the potential to create winners and losers in investment markets, says Ackman.

Companies that can reduce their emissions significantly will have the upside of a new revenue source from selling excess carbon credits.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund

An Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

Others face the risk of significant penalties if they don’t invest in cutting their emissions intensity.

“As a fixed income investor, we actually get quite good access to some of these emitters.

“A thorough understanding of a business and its transition plan is important for investors.

“It’s one thing looking at the balance sheet today.

But you also want to know how earnings will be able to be maintained over the policy cycle.”

About Murray Ackman and Regnan

Murray is a Senior ESG and Impact Analyst with sustainable investing leader Regnan.

He also provides fundamental credit analysis on Environmental, Social and Governance factors for Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

Murray has worked as a consultant measuring ESG for family offices and private equity firms and was a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace where he led research on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Find out more about Regnan here

Regnan Credit Impact Trust is an investment strategy that puts capital to work for positive change.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund is an Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.

Pendal’s ESG scorecard measures credit risk on state government bonds. MURRAY ACKMAN explains how it works

- ESG factors help understand risk of bond downgrade

- Find out about Regnan Credit Impact Trust

- Find out about Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest fund

IF you’re investing in state government bonds, you’re probably not too worried about default.

But you might be concerned about a potential credit downgrade – which could result in lower demand for a bond and a drop in its value.

Pendal’s income and fixed interest team has a tool to assess the ESG credentials of state governments – which can help highlight credit risks that might lead to ratings downgrades.

The Australian States SDG Index assesses how each state is addressing the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals – a list of the world’s biggest problems.

The ACT, Tasmania and South Australia lead the index, while Western Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory lag, says Pendal ESG credit analyst Murray Ackman.

“People always talk about default — the risk of not getting your money back,” says Ackman.

Find out about

Regnan Credit Impact Trust

“But that’s not all we’re looking at.

“There would have to be something catastrophic for a state government not being able to service its debt.

“What does have an impact on your investment is credit downgrades.”

How it works

The index scores the states on 70 indicators across 16 environmental and social themes.

It assesses how states perform on factors like healthcare and education spending, climate action, water and sanitation and justice and strong institutions.

Ackman uses the example of ratings agencies downgrading Queensland more than a decade ago after it slid into deficit on the back of a big spending program on water security.

“There was a longstanding underspend on water security, so a lot of money had to be spent on a desalination plant. ESG can give us an early warning sign of these kind of issues.”

Today, Ackman says there are signs of underspending in Victoria on health and well-being and in the Northern Territory on justice and strong institutions.

These could flag future problems, he says.

On the upside, the index shows strong environmental scores in the ACT and Tasmania, both already using a high proportion of renewable energy which reduces the risk of the energy transition.

Ackman says ESG scoring also provides an opportunity to engage with governments and seek to directly drive change — even although governments can be less responsive than corporations to the views of the investment community.

“Engaging with a company can be pretty obvious — one has better human rights policies, another might have good oversight of their supply chain and slavery. You can compare the two and make a decision to engage or divest.

“But government bonds are different. Commonwealth government bonds are more than half the index for some of our fixed interest funds.

“We can engage — and we’re pushing for green issuance and we want to see new projects being funded — but we don’t realistically have the opportunity to divest. Having genuine influence over an issuer would require being willing to walk away.”

He says Pendal’s ESG scoring also allows investors to be sure their money is being invested in line with their intentions.

“Our investors want their values reflected in the investment decisions that we make.”

About Murray Ackman and Regnan

Murray is a Senior ESG and Impact Analyst with sustainable investing leader Regnan.

He also provides fundamental credit analysis on Environmental, Social and Governance factors for Pendal’s Income and Fixed Interest team.

Murray has worked as a consultant measuring ESG for family offices and private equity firms and was a Research Fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace where he led research on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Find out more about Regnan here

Regnan Credit Impact Trust is an investment strategy that puts capital to work for positive change.

Pendal Sustainable Australian Fixed Interest Fund is an Aussie bond fund that aims to outperform its benchmark while targeting environmental and social outcomes via a portion of its holdings.